Jane Davis is the author of seven critically acclaimed novels, one of which, Half-truths and White Lies, won The Daily Mail First Novel Award.

Jane Davis is the author of seven critically acclaimed novels, one of which, Half-truths and White Lies, won The Daily Mail First Novel Award.

Today she drops by to discuss writing craft and the extensive research that led to her latest book, My Counterfeit Self, which I read on my recent long-haul travels.

Lucy, the main character is a poet and campaigner with a complex love life, living in London in the swinging Sixties. As I flew over the vast swathe of desert in South Australia, it dawned on me that somewhere below me was Maralinga. If you’ve never heard of it, that’s because since then, the British government has done everything it can to avoid compensating all those who were forced to witness its programme of nuclear testing in the 1950s.

South Australia, Desert

Before we discussed Lucy’s life as a poet and activist, as I read the book, it occurred to me that Lucy was fortunate to even make it to adulthood. As child she suffered from polio and was forced to undergo a form of solitary confinement in what was known as an ‘iron lung’. I can recall reading a story when I was young, about a girl who was in one. I was both terrified and fascinated at her plight. I hoped fervently it would never happen to me.

On craft

I am fascinated by young Lucy, and I highlighted this sentence: ‘just the living breathing gasping machine and the silent stiff necked girl.’ The ill girl, incarcerated, who found a way to pass the time, by developing a vivid inner life. To paraphrase Beryl Bainbridge, novelists need to be able to mine the imagination they once had as children. With this in mind, can you describe the process of creating young Lucy?

The line you’ve chosen describes Lucy, alone, in her iron lung, while she’s undergoing treatment for polio. I was inspired by a documentary about Jim Marshall, inventor of the Marshall amp and became fascinated by childhood illness. He had tubercular bones, then potentially fatal, and as a result, spent his childhood cocooned in plaster casts and in and out of hospital. It was his father who suggested he try tap dancing as part of his physical recovery. That helped give him an incredible ear for rhythm, he became a drummer, a drum teacher, and the rest is history. It’s impossible to say how differently Jim’s biography would have read if he hadn’t contracted the disease, but it’s fair to assume he was changed by it.

The focus of most of the articles I read about childhood illness and disabilities was its impact on families. Warnings that parents shouldn’t superimpose their fears onto the child, reports on the stress levels of mothers who had children who were ill or disabled, financial impact on families, mortality rates, etc. Surprisingly little appears to have been published about what the child actually suffering the illness was going through. All I could do was put myself in Lucy’s shoes and get a real sense of who she was.

Staring death in the face alters a person’s perception, whatever their age happens to be. Although she isn’t paralysed, I gave Lucy that same determination Roosevelt displayed when he refused to accept the limitations of his disease. The refusal to wear leg braces, to face the world sitting down. She also resents overhearing her father say that not much is expected of her, and it makes her want to defy him. She becomes driven. I think survivors need a good healthy stubborn streak.

But, strange though it sounds, my starting point for Lucy the child was Lucy as an old woman. I had the opening scene. An elderly, eccentric-looking woman, standing in the middle of her rose garden, furious to discover that she’s been nominated for a New Year’s honour. I wanted to know who she was and what had made her that way.

My Counterfeit Self FB Ad

I’ve read My Counterfeit Self as well as An Unknown Woman, and it seemed to me, that how you tell the tale and in what order, is as important the story itself. Do you plan the structure of your story before you write it, or does this evolve during the writing of the first draft?

I allow the characters to take charge. The story always reveals itself to me in the process of writing it, and the purpose of the story may not reveal itself until I’m many drafts in. In fact, the two novels you mention are quite different in terms of structure. An Unknown Woman sticks to a chronology and makes use of backstory, but I’m a huge fan of the non-linear structure, which I use for My Counterfeit Self.

Sometimes a book demands to be told in a particular order, because in fiction the big reveal must come near the end of the novel but in life the pivotal event tends to have a habit of showing up early. What excites me is cause and effect, how the past impacts on the present. Memories don’t always arrive in chronological order. They show up like photographs or postcards, or sometimes even like unwelcome guests. With a deconstructed timeline, the reader gradually builds a picture of who the angry old lady we meet in the first chapter is, and what made her that way. The story comes together like a mosaic.

On research

Confinement, through illness, in Lucy’s case, (or boarding school in mine) can be a catalyst for a vivid imagination. It’s one way of coping with the fear and despair of the situation. As your physical world shrinks, your imagination is one of the few remaining senses you have left. Is this why you made Lucy a poet (rather than a novelist or musician?). Or was it for other reasons? And was poetry an art form you practice, or did you have to learn fast?

I have a confession to make. The idea of writing about the life of a poet came from readers. So many reviews had commented that my prose was like poetry, it gave me confidence that I could convince readers I could see the world the way a poet does. As for the poetry, I decided that the worst possible thing I could do for the book would be to write it myself. Instead, I commissioned a poet to write several pieces. Unfortunately, that arrangement fell through at the eleventh hour. By that time, my copy editor had done his worst and encouraged me to have a stab at it. After all, I knew how Lucy thought. This was fairly daunting. After all, the novel makes some fairly outrageous claims about Lucy’s abilities. It refers to her as Britain’s greatest living poet, for goodness sake! I thought, I’ll only be able to get away with this if I limit myself to writing Lucy’s childhood poems. So that’s what I did. I think they’re just about passable as the work of a ten-year-old.

The old way of treating polio, where children were physically incarcerated, must be confronting to some readers, who might not know about it. What has been the response? And how did you go about researching it?

To be honest, I didn’t expect any particular reaction to my portrayal of Lucy’s illness, although I did receive feedback from a nurse who said that, with her knowledge of treating children with polio, she really understood Lucy’s motivations. (The same reader also sent me wonderful newspaper clippings about her political activist aunt who had recently died at the age of 93). Another reader has told me that I’ve written her early biography – the part that takes Lucy from polio to political activism. It interesting, the idea that you could inadvertently write someone’s biography, but I suppose if you get your research right, and the sense of the time right, that will eventually happen.

As you’ve mentioned yourself, it was how Lucy dealt with isolation that interested me as much as her illness. For research, I started in the usual way, with a Google search. I also have a marvellous friend, someone I admire tremendously, who had childhood polio and who shared his experience with me and was willing to answer specific questions. Then there was the film of Ian Dury’s life, Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, which actually shows much harsher treatment than I portrayed, and made me wonder if I was going far enough.

The romantic love triangle storyline gives us the counterfeit self of the title. Can you describe this notion of the counterfeit self?

Lucy’s parents behave appallingly and in such a way that frees her from any feeling of obligation to live up to their expectations. She moves out of the family home and decamps to bohemian Soho. In distancing herself from her parents she adopts a new personality that she hides behind, her counterfeit self. Although she insists that she lays herself bare in her poetry, it’s keeping secrets from those who love her most that is her undoing.

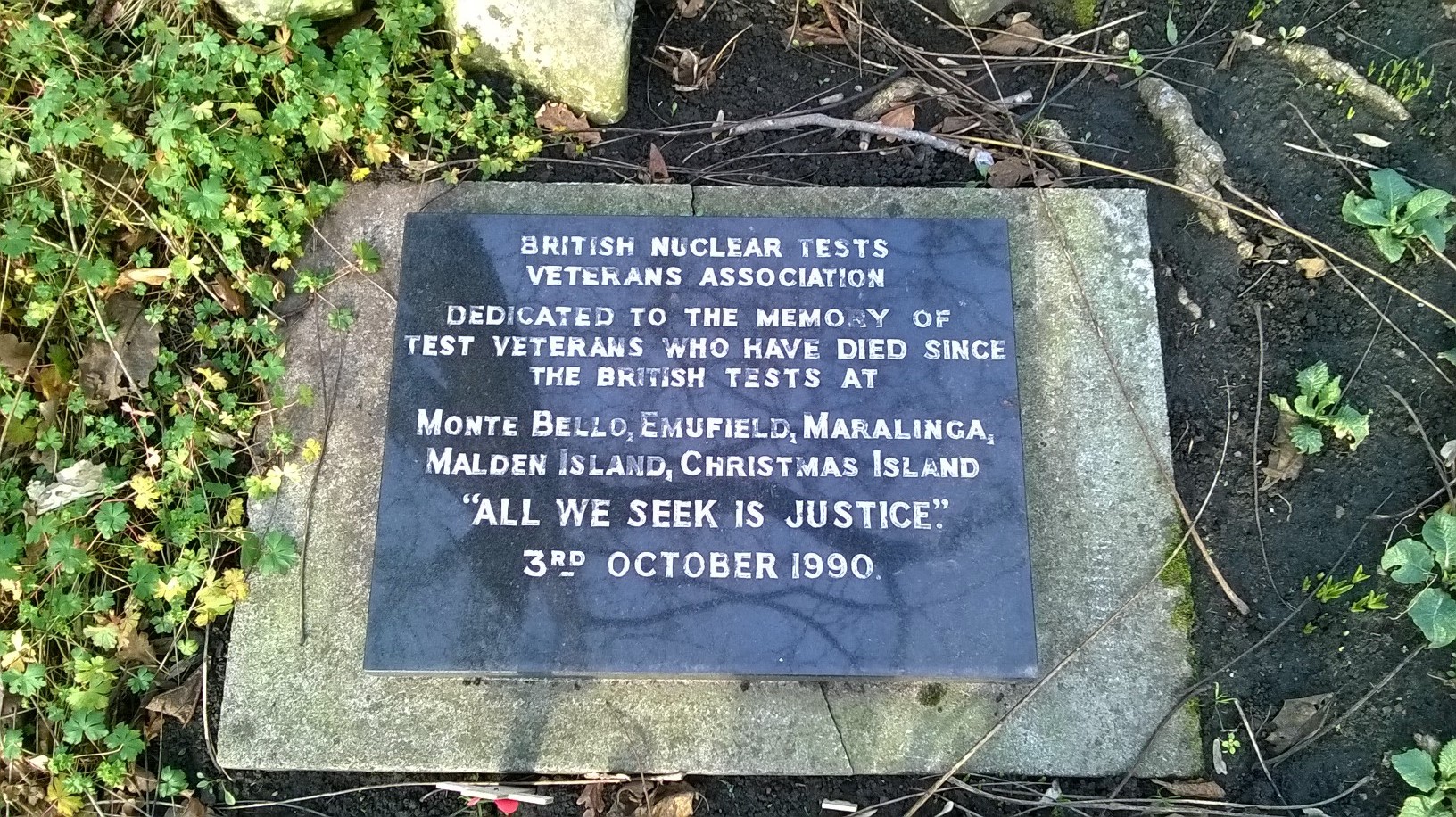

The adult Lucy is as much campaigner as she is a poet. For someone who hasn’t read your book, can you describe what it was that led Lucy to campaign for British servicemen, (many of who were conscripted), who were forced to take part in nuclear testing in the 1950s and 60s.

Lucy is my rebel with a cause. When I laid her lifespan over a historical timeline, there was only one choice of what that cause would be. Fear of the Nuclear Bomb was a hangover from her wartime childhood. Talk of a third world war – the war to end all wars – permeated her adolescence. Bring her governess Pamela into the equation, a young woman who was prepared to take a stand, and of course Lucy was hooked. Watching black and white footage of Rod Stewart taking part in the first of the CND rallies and marches from Trafalgar Square to Aldermaston brought it together for me. I had no trouble imagining Lucy Forrester there at the centre of it all. And, of course, if you’ve campaigned for CND your entire adult life, it seems natural that you would take up the cause of the atomic veterans when their plight was highlighted.

British Nuclear Tests Veterans memorial

On leading a writing life

I love the Emily Dickinson line you quote: ‘I’m nobody. Who are you?’ Can you elaborate on that notion of poet and writer as a misfit?

I can only comment on Lucy who, set apart during her illness, both literally and figuratively, became the misfit in her own home. In Lucy’s case, I also wanted to give an idea of physical separation, a life lived on the attic floor of her parents’ home, her sense of abandonment, which leads to a fear of abandonment in later life. She calls herself the Out of Sight Out of Mind Child. But there are advantages to being a misfit. Master the art and you learn not to mind standing out. You learn not to mind standing up and being counted, which, of course Lucy becomes very good at. An early reviewer called her ‘fiercely moral’, which I liked very much indeed.

You write, ‘attack came from all angles, leaving little creative thinking time.’ How do you manage to balance your writing time with the need to earn a living, marketing and find time for a home life?

Very badly, if the truth be known. There is no downtime. Trying to find a better balance is top of my of New Year’s Resolutions. I’ll let you know how I get on!

Jane Davis is the author of seven novels. Her debut, Half-truths and White Lies, won the Daily Mail First Novel Award, and The Bookseller featured her in their ‘One to Watch’ section. Six further novels have earned her a loyal fan base and wide-spread praise. Her 2016 novel, An Unknown Woman, won Writing Magazine’s Self-Published Book of the Year Award. Compulsion Reads describe her as ‘a phenomenal writer whose ability to create well-rounded characters that are easy to relate to feels effortless.’ Her favourite description of fiction is ‘made-up truth’.

When Jane is not writing, you may spot her disappearing up the side of a mountain with a camera in hand.

Universal Buy Link: https://books2read.com/u/4AgQdK

My website: www.jane-davis.co.uk

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JaneDavisAuthorPage/?fref=ts

Twitter: https://twitter.com/janedavisauthor

Google Plus: https://plus.google.com/+JaneDavisAuthor/posts

Pinterest: https://uk.pinterest.com/janeeleanordavi/boards/

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/6869939.Jane_Davis

Amazon Author Page:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Jane-Davis/e/B0034P156Q/ref=ntt_athr_dp_pel_pop_1

You can find out more about the Atomic Veterans or make a donation here.

Anyone who signs up to Jane’s newsletter receives a free copy of her novel, I Stopped Time. Jane promises not to bombard subscribers with junk. She only issues a newsletter when she has something genuinely newsworthy to report.

Alison Ripley Cubitt is an author, memoirist, novelist and screenwriter. She co-writes thrillers as Lambert Nagle.

I could not resist commenting. Perfectly written!

Thank you so much Alison. So interesting to hear your perspective on Maralinga. I hope I did your questions justice.

Thank you, Jane. Your answers were fascinating. I really enjoyed your

answers on character development.